2026/01/03 Sakae Kumehara

- Collatz operation

- summary

- Prove the following:

- Collatz operation by type

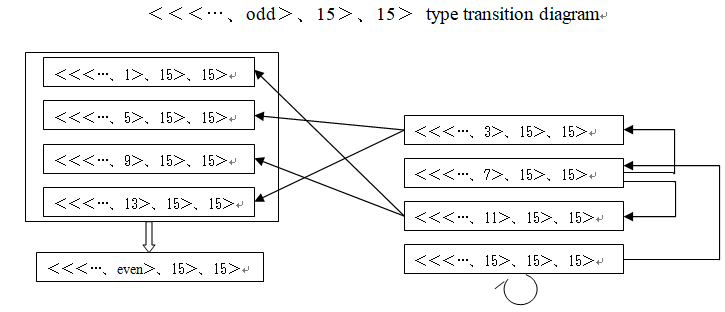

- type transition diagram

- Type for integers with 3 or more digits and whether the second is even or odd

- Contraction and expansion due to type changes

- Starting with integers of type 1, type 5, type 9, type 13

- Starting with integers of type 3

- When starting with integers of type 7

- When starting with integers of type 11

- When starting with integers of type 15

- Review of items left on hold

- Ratio of even and odd numbers in the second digit

- Let’s try adding more digits.

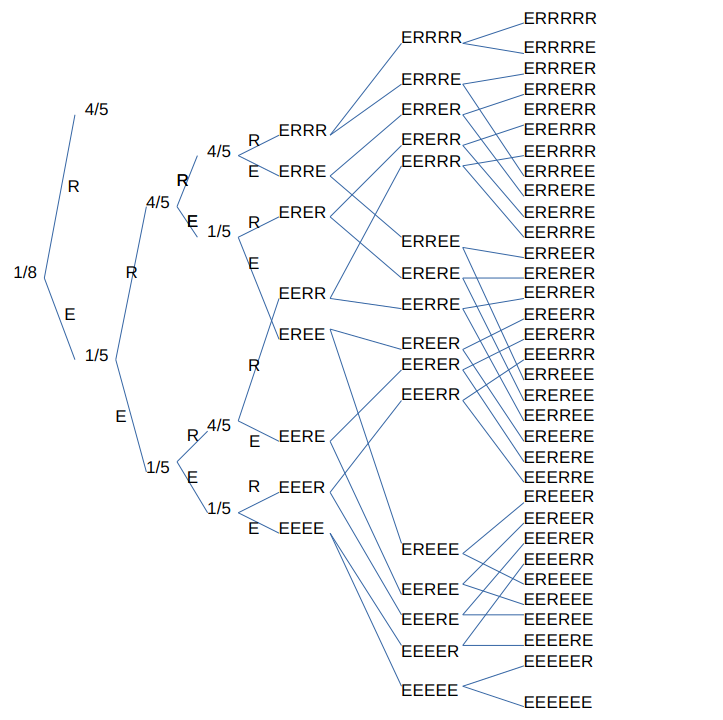

- What happens to even and odd numbers in the processing of (3n+1)/2 and /2?

- Tracking the extended column further

- Modeling Type 7 and Type 11

- Transition from 15 Types

- Considerations Regarding Consecutive Occurrences of 15 Starting from the Least Significant Digit

- Breaking away from the Type 15 series

- Considerations Regarding the 15 in the Middle of the Digits

- Transition from other types to Type 15

- Conclusion

Collatz operation

The Collatz conjecture asserts that starting with any positive integer n, if n is even, divide it by 2; if n is odd, multiply it by 3 and add 1. Repeating this process will eventually lead to 1 after a finite number of steps, no matter where you start.

summary

Any positive integer can be expressed as an16n+an-116n-1+…+a116+a0, where 16 is the base (and an, an-1, … a1, a0 are integers ranging from 0 to 15). For any given positive integer, when performing the Collatz operation, if the integer is even, we perform the process of “dividing by 2” as many times as the number of factors 2 contained within that even number, and then extract the odd number. Let us consider this as a preprocessing step for the Collatz operation. This means that the Collatz operation will only be applied to odd numbers. Of course, even numbers may appear during the course of the computation. For an odd integer n, we operate (3n + 1) / 2. If the resulting answer can undergo another “divide by 2” operation, we perform that operation to remove the factor 2 from the answer. This entire sequence of operations constitutes one iteration of the Collatz operation.

When representing the Collatz operation’s subject as an odd number using base-16 notation, it can be classified by the number of its least significant digits. That is, every positive odd number can be divided into eight types: Type 1, Type 3, Type 5, Type 7, Type 9, Type 11, Type 13, and Type 15.

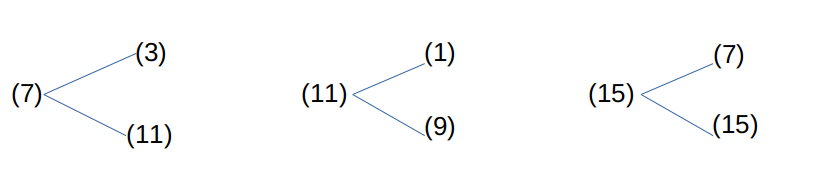

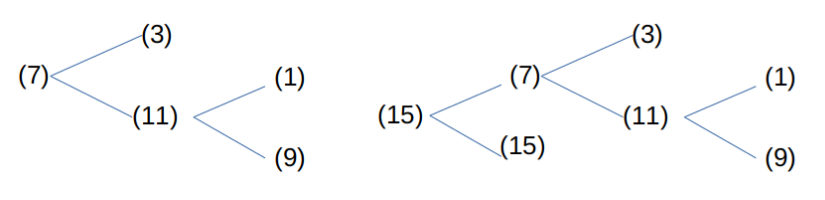

Applying the Collatz operation to any integer results in the same behavior for each type. It then transitions from one type to another. Which type it transitions to is determined by whether the second digit is even or odd. This type of transition can be represented as a graph. This is referred to in this paper as the type transition diagram. The type transition diagram graphically shows which type transitions to which other type. When transitioning from one type to another, there are several possible branches. These include cases where the transition branches into two, four, or eight different paths.

The types that branch into two are Type 3, Type 7, Type 11, and Type 15. When applying the Collatz operation to integers, a single branch typically results in a factor of 3/2. Therefore, when a branch splits into two, it is fundamentally multiplied by 3/2. When passing through Type 3, Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15, the number is fundamentally multiplied by 3/2. When branching into four paths, the first branch occurs via the (3n+1)/2 operation. The subsequent branch is merely an internal division by 2 within the type. Thus, when branching into four paths, the result is multiplied by (3/2 x 1/2 = 3/4), effectively reducing the value to 3/4. The types that branch into four paths are Type 1 and Type 9. When branching into 8 paths, the initial (3n+1)/2 processing plus two subsequent internal “divide by 2” operations occur, resulting in “3/2 x 1/2 x 1/2 = 3/8”. Type 13 branches into 8. Furthermore, for Type 5, the internal processing is “1/2 x 1/2 x 1/2”. Combined with 3/2, this results in a multiplication by 3/16. Regarding Type 3, since it branches into either Type 5 or Type 13, it is an expanding type. However, when combined with the processing of Types 5 and 13, it becomes a shrinking type overall. Based on the above, tracing the branches reveals that applying the Collatz operation starting from Types 1, 3, 5, 9, or 13 converges to a multiplier of 1 or less. Furthermore, it was proven that Types 7 and 11 also converge to a multiplier of 1 or less. Furthermore, it was proven that the remaining Type 15, as long as it is a finite integer, eventually transforms into Type 7. Therefore, it was established that all integers converge to integers smaller than the starting integer in the Collatz operation. Additionally, it was proven that all two-digit integers become 1 through repeated Collatz operations. Consequently, it was found that applying the Collatz operation sequentially, starting from small integers, results in all integers becoming 1.

Prove the following:

Any integer can be expressed as an16n+an-116n-1+…+a116+a(where an,an-1, …a1,a0 are integers ranging from 0 to 15).

However, if the integer is even, dividing it by 2 yields a value less than or equal to half the starting integer of the Collatz process. By proving that selecting starting integers in ascending order converges to 1, we see that if an integer becomes smaller than its starting integer, it must already be among the proven integers. Therefore, we focus on odd integers and prove convergence to the set of proven integers.

All positive odd integers can be expressed as 16p+1, 16p+3, 16p+5, 16p+7, 16p+9, 16p+11, 16p+13, 16p+15, and we will consider these as types. That is, we classify all numbers into Type 1, Type 3, Type 5, Type 7, Type 9, Type 11, Type 13, and Type 15, and apply the Collatz operation to these.

An arbitrary positive number can be expressed as an16n+an-116n-1+…+a116+a0(suppose an, an-1, … a1, a0 is an integer between 0 and 15). Now we consider two-digit odd numbers because, being divided by 2 repeatedly, even numbers become odd numbers less than half. If we select integers to be subjected to the Collatz operation in ascending order and prove them, all even numbers will be reduced to integers that have already been proven. Therefore, from here on, we will only choose odd numbers as the target for the Collatz operation and prove that they converge to 1.

If the last two digits of all odd numbers are expressed as 16p+q, then all odd numbers can be classified as 16p+1, 16p+3, 16p+5, 16p+7, 16p+9, 16p+11, 16p+13, and 16p+15.

Collatz operation by type

In this section, we will simplify 16p+n and denote it as (p, n) or <p, n>. Here, the “divide by 2” step in the Collatz process is represented by “→”. Note that even when the division by 2 occurs multiple times consecutively, it may be represented by a single “→”.

Here, during the Collatz process, if the least significant digit is even, we denote it <p, n> to indicate it is still in progress. When the least significant digit becomes odd, signifying the completion of one Collatz iteration, we use the notation (p, n).

● case of type “1.”

3(p、1)+1=<3p、4>

if p is even,<3p、4>→<divide by 2>→<q、2>

if q is even,<q、2>→<divide by 2>→(r、1)

if q is odd, <q、2>=<q-1、18>→<divide by 2>→(r、9)

if p is odd,<3p、4>=<3p-1、20>→<q、10>

if q is even,<q、10>→(r、5)

if q is odd,<q、10>=<q-1、26>→(r、13)

● case of type “3.”

3(p、3)+1=<3p、10>

if p is even,<3p、10>→(q、5)

if p is odd,<3p、10>=<3p-1、26>=(q、13)

● case of type “5.”

3(p、5)+1=<3p、16>=(3p+1、0)=16(3p+1)→3p+1

<3p+1, 0> is type 0 in the classification by type. If the least significant digit becomes 0 during the operation, <3p+1, 0> = 16(3p+1)+0 = 16(3p+1) → 8(3p+1) → 4(3p+1) → 2(3p+1) → (3p+1). This shifts the entire digit sequence one place to the left. Since the multiplier is becoming <0, 3p+1>, the result is approximately 3/16. However, (3p+1) may contain the factor 2, potentially reducing the multiplier further.

● case of type “7.”

3(p、7)+1=<3p、22>

if p is even,<3p、22>→(q、11)

if p is odd,<3p、22>=<3p+1、6>→<q、3>

● case of type “9.”

3(p、9)+1=<3p、28>

if p is even,<3p、28>→<q、14>

if q is even,<q、14>→(r、7)

if q is odd,<q、14>=<q-1、30>→(r、15)

if p is odd,<3p、28>=<3p+1、12>→<q、6>

if q is even,<q、6>→(r、3)

if q is odd,<q、6>=<q-1、22>→(r、11)

● case of type “11.”

3(p、11)+1=<3p、34>

if p is even,<3p、34>→<q、17>=<q+1、1>

if p is odd,<3p、34>=<3p+1、18>→<q、9>

● case of type “13.”

3(p、13)+1=<3p、40>=

if p is even,<3p、40>→<q、20>

if q is even,<q、20>→<r、10>

if r is even,<r、10>→(s、5)

if r is odd,<r、10>=<r-1、26>→(s、13)

if q is odd,<q、20>=<q+1、4>→<r、2>

if r is even,<r、2>→(s、1)

if r is odd,<r、2>=<r-1、18>→(s、9)

if p is odd,<3p、40>=<3q+1、24>→<q、12>

if q is even,<q、12>→<r、6>

if r is even,<r、6>→(s、3)

if r is odd,<r、6>=<r-1、22>→(s、11)

if q is odd,<q、12>=<q-1、28>→<r、14>

if r is even,<r、14>→(s、7)

if r is odd,<r、14>=<r-1、30>→(s、15)

● case of type “15.”

3(p, 15) + 1 = <3p, 46>

if p is even,<3p、46>→<q、23>=<q+1、7>

if p is odd,<3p、46>=<3p+1、30>→<q、15>

Based on the above analysis, for Types 7, 11, and 15, applying the Collatz operation once results in a factor of 3/2, and the second-digit coefficient may exceed 16. However, no special consideration is given to this point. If the second-digit coefficient exceeds 16, one might consider introducing a notation like <<a2+1, a1<, a0> to account for carry to the third digit. However, this will be addressed later. For now, to focus on type transitions, carry to the third digit is ignored. This is because, in the type transition diagram shown next, the minimum digit and the number in the second-to-last digit are critically important.

type transition diagram

Based on the above analysis, the type transition diagram is as follows.

Type for integers with 3 or more digits and whether the second is even or odd

When considering type transitions, it has become clear that the type and the evenness or oddness of the second digit play a critically important role. Thus far, we have discussed two-digit integers, but we wish to extend the discussion to integers with three or more digits.

The digit in the second-to-last position reflects the result of fine-tuning when performing the “divide by 2” operation. Since we have already explained the processing for cases where the least significant digit is even and the second digit is odd, let us now consider the case where the least significant digit is even, and the third digit from the bottom (the third digit) is odd. Here, we are considering the case where the least significant digit is even and the second digit is also even. We will not question here whether the second digit was even from the start or became even as a result of the adjustment. When the third digit is odd, either subtract 1 from the third digit and add 16 to the second digit, or add 1 to the third digit and subtract 16 from the second digit. For Type 3, Type 7, Type 11, and Type 15, where the “divide by 2” operation occurs once, this operation leaves a result of either “+8” or “-8”. That is, assuming the result of processing a two-digit integer leaves the second digit as “m”, factoring in the adjustment with the third digit results in either “m+8” or “m-8”. The parity of “m” and the parity of “m+8” or “m-8” are the same. However, the parity of “m” is considered resolved during the processing of the two-digit integer and is not addressed here. The discussion here concerns the carry from the third digit or the borrow into the third digit, and the resulting “+8” or “-8” applied to the second digit.

Type 1 and Type 9, which require two “divide by 2” operations, have the same state during the first “divide by 2” operation as when only one “divide by 2” operation is needed. If a carry occurs during the first operation, the result is “n-8”. If a carry occurs during the second “divide by 2” operation, the carry value “-16” is added to this result, and this sum is then divided by 2. Thus, the result becomes “n-4-8”. Note that here too, n is assumed to be the second digit of the two-digit Type 1 and Type 9 integers after the “divide by 2” operation. Therefore, “-4-8” represents the difference between applying the Collatz operation to a two-digit integer and applying it to a three-digit or larger integer. Similarly, depending on whether the first step produces a carry or a borrow, and whether the second step produces a carry or a borrow, four possible results are obtained: “n-4+8”, “n+4-8”, and “n+4+8”. If there is no carry or borrow during the second “divide by 2” operation, the result is either “n+4” or “n-4”. It can be seen that whether n is even or odd corresponds to “n-4-8”, “n-4+8”, “n+4-8”, “n+4+8”, “n+4”, “n+4”, and “n-4”.

In Type 13, which requires three “divide by 2” operations, if the second digit is s when the third operation is performed as a two-digit integer, then “s-2-4-8”, “s-2-4+8”, “s-2+4-8”, “s-2+4+8”, “s+2-4-8”, “s+2-4+8”, “s+2+4-8”, “s+2+4+8”. If there is no carry or borrow, it becomes “s-2-4”, “s-2+4”, “s+2-4”, “s+2+4”. If there is no carry or borrow in either the second or third step, it becomes “s-2”, “s+2”, and the even/odd nature of the second digit is the same as when it is “s”. Of course, looking at the type transition table, type 13 branches into <s, 1>, <s, 9>, <s, 5>, <s, 13>, <s, 3>, <s, 11>, <s, 7>, <s, 15>, and, while the value of “s” differs in each case, the evenness/oddness remains unchanged. That is, depending on the parity of “s”, the parity of the sequences “s-2-4-8”, “s-2-4+8”, “s-2+4-8”, “s-2+4+8”, “s+2-4-8”, “s+2-4+8”, “s+2+4-8”, “s+2+4+8”, “s-2-4”, “s-2+4”, “s+2-4”, “s+2+4”, “s-2”, “s+2” are determined.

As a result of the above analysis, the type transition diagram described in the previous section can be applied directly to integers with three or more digits.

Contraction and expansion due to type changes

Each time you perform a Collatz operation, the value in the least significant digit changes. The course on the type transition diagram changes depending on the number of the least digit and whether the second digit is even or odd. Here, we verify how the integer value increases or decreases with each branch on the type transition diagram, and show the multiplier for the starting integer. The least significant digit (type) is represented by (n), and the change from type (n) to type (n+2) is defined by (n)(n+2).

If the magnification becomes 1 or less, it is determined that the integer is smaller than the starting integer, and verification is stopped. If the proof proceeds by proving the Collatz conjecture to be true starting from a smaller integer, then once the value becomes smaller than the starting point, it will have been reduced to a proven integer.

It was proven that by applying the Collatz operation to the integers from (0, 3) to (15, 15), all of them converge to 1. <click here>

Starting with integers of type 1, type 5, type 9, type 13

Starting with type 1 integers

(1)(1): 3/4

(1)(5): 3/4

(1)(9): 3/4

(1)(13): 3/4

If we start with type 1 integers, we transition to (1), (5), (9), or (15)

Starting with type 5 integers

When starting from an integer of type 5, the process in (5) multiplies it by 3/16, so it converges to a proven integer smaller than the starting integer.

Starting with type 9 integers

(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/4

If we start from (9), we then transition to (3), (7), (11), or (15), which reduces it to a 3/4th of a factor, and so to an integer that has already been proven. In the future, when branching from (n) to (n+2) or (n+4), to simplify the expression, we may use “|” and write it as (n)-(n+2)|(n+4).

Starting with type 13 integers

(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/8

If (13) is the starting point, the transitions will be (1), (9), (5), (13), or (7), (15), (3), (11). The branch from (13) to (1)|(9)|(5)|(13) is the same as the branch from (1) to (1)|(9)|(5)|(13), and the branch from (13) to (7)|(15)|(3)|(11) is the same as the branch from (9) to (7)|(15)|(3)|(11). In either case, two branches are performed during type 13 processing, resulting in two divisions, which yield a total multiplication of 3/2 x 1/2 x 1/2 = 3/8. Therefore, in either case, we can see that the sequence converges to a previously proven integer that is smaller than the starting integer.

Starting with integers of type 3

Transitions starting from (13) lead to either (5) or (13).

When transitioning from (3) to (5), the process within (5) reduces the value by 3/16, resulting in a combined effect of 3/2 x 3/16 = 9/32.

(3)(5): 3/2 x (3/16) = 9/32

When transitioning from (3) to (13), the value is multiplied by 3/8 during the processing of (13), resulting in a total of 9/32. This ensures convergence to a proven integer.

(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/8 = 9/16

When starting with integers of type 7

When starting with integers of types 1, 3, 5, 9, 13, we found it easy to reduce to integers smaller than the starting integer. But what about types 7, 11, and 15? Let’s start by checking type 7.

Looking at the type transition diagram, we can see that when starting from a type 7 integer, it transitions to either type 3 or type 11.

When starting the Collatz process from type 7 and following type 3, it further transitions to type 5 or type13. When transitioning to type 5, the value is multiplied by 3/2 during type 5 processing. Taking this into acount, (7)(3)(5) = 3/2 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 9/64.

Starting from type 7 and progressing through type 3 to type 13, considering that the integer being manipulated is multiplied by 3/8 within type 13, the result is as follows.

(7)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 27/32

(7)(3)(13)(3): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 27/32

As shown above, when transitioning from type 7 to type3, it can be seen that in all cases, the integer being manipulated reduces to an integer that has already been proven to be smaller than its initial value.

When departing from type 7 and passing through type 11, the pass subsequently branches to either type 1 or type 9. At this branching point, the transition from type 7 to type11 results in a multiplication factor. Subsequently, the transitions to type 1 and type 9 each apply a 3/2 multiplication factor. Furthermore, type 1 transitions to types 1, 5, 9, and 13, while type 9 transitions to types 3, 7, 11, and 15.

Furthermore, considering that the internal processing during branching from type 1 to types 1, 5, 9, and 13 is multiplied by 1/2, the total transition from type 7 becomes 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 27/16.

(7)(11)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 27/16

The same applies when progressing from type 7 integers to type 11, and then to type 9.

(7)(11)(9)(3): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 27/16

(7)(11)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 27/16

For those ending in type 1, 5, 9, 13, and 3, since there is an internal division by 2, it may be possible to prove that they decrease easily. The simplest case is when type 5 continues. In type 5, the value is internally multiplied by 3/16. Taking this internal processing into account, (7)(11)(1)(5): 27/16 x (3/16) = 81/256. Furthermore, since type 13 performs two internal “divide by 2” operations, considering this, the transition from type 13 to the next (1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15) results in a 3/8 multiplication. Therefore, (7)(11)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 27/16 x 3/8 = 81/128.

What about branching to type 3? In type 3, the internal processing of “divide by 2” is not performed, but since it subsequently branches to either type 5 or type 13, it holds great promise.

When branching to type 5, the calculation result is as follows.

(7)(11)(9)(3)(5): 27/16 x 2/3 x (3/16) = 243/512

When branching from type 3 to type 13, it branches to one of the following types: (1), (3), (5), (7), (9), (11), (13), (15). In the branch from (3) to (13), it is multiplied by 3/2. Furthermore, in any branch from (13) to (1), (3), (5), (7), (9), (11), (13), or (15), it is multiplied by 3/8 (equivalent to 3/2 x 1/2 x 1/2). Therefore, the result is as follows.

(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 27/16 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 243/256

Therefore, in either case, it converges to a previously proven integer that is smaller than the starting integer.

(7)(11)(1)(1), (7)(11)(1)(9) also show some promise, as the internal processing continues to branch to type 1 or type 9, which perform a single division by 2.

First, let’s confirm (7)(11)(1)(1).

(7)(11)(1)(1)(1): 27/16 x 3/4 = 81/64

(7)(11)(1)(1)(5): 27/16 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 243/1024 : multiplied by 3/16 during internal processing of type 5

(7)(11)(1)(1)(9): 27/16 x 3/4 = 81/64

(7)(11)(1)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/8 = 243/512

(7)(11)(1)(1)(1) and (7)(11)(1)(1)(9) are still expanding. Next, type 1 branches into (1)|(9)|(5)|(13), and type 9 branches into (7)|(15)|(3)|(11). Considering this, the following holds:

(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 81/64 x 3/4 = 243/256

The same applies to the branching from type 9.

(7)(11)(1)(1)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 81/64 x 3/4 = 243/256

Next, we will also examine (7)(11)(1)(9). Type 9 subsequently branches into (7)|(15)|(3)|(11). While (7), (11), and (15) expand, the branch to (3) contracts. Therefore, let us examine (7)(11)(1)(9)(3). Type 3 subsequently branches into either type 5 or type 13.

The branching calculation for type 5 is as follows.

(7)(11)(1)(9)(3)(5): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 729/2048

The branch to type 13 then splits (1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15), and since it is internally scaled by 3/8 at that point, it becomes as follows.

(7)(11)(1)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 729/1024

As a result, we are unable to prove that (7)(11)(1)(9)(7), (7)(11)(1)(9)(11), and (7)(11)(1)(9)(15) have a multiplier of 1 or least, leaving them as remaining cases. Furthermore, (7)(11)(9)(7), (7)(11)(9)(11), and (7)(11)(9)(15) remain. For (7)(11)(1)(9)(7), since it has reverted to type 7, the calculations performed thus far will be repeated exactly as they were. For example, even if a sequence showing a tendency to converge follows (7)(11)(1)(9)(7), if it is (11)(1)(1)(9)(7), then (7)(11)(1)(1)(9)(7): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 243/256. Since the contraction trend is not very large, the total becomes 81/64 x 243/256 = 19683/16384, meaning it cannot escape the expansion trend. After (7)(11)(1)(9)(7), if (11)(1)(9)(3)(13) follows, then (7)(11)(1)(9)(3)(13)- (1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 729/1024. Therefore, the total is 81/64 x 729/1024 = 59049/66176, which converges to a proven integer smaller than the starting point. In other words, even for processing sequences that were held in reserve, assuming the expansion trend would continue, subsequent additions to the processing sequence could result in the multiplier falling below 1. Consequently, any processing sequences that fail to achieve a multiplier of 1 or less would require further processing.

When starting with integers of type 11

Type 11 subsequently transitions to either type 1 or type 9. The transition rate from type 11 to both type 1 and type 9 increases by a factor of 3/2. However, transitioning from type 1 to (1), (5), (9), (13) and from type 9 to (3), (7), (11), (15) results in 3/2 x 1/2 = 3/4 in each case. Therefore, the total is 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8, showing a slight increase.

(11)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13) : 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8

(11)(9)(3)-(3): 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8

(11)(9)(3)-(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8

When starting from type 11 integers, each case involves a slight expansion. Therefore, it is easy to predict that when followed by the contraction-prone type (1), (3), (5), (9), and (13), a contraction will readily occur. This is because, for types 1 and 9, the internal branch halves the value only once, and when combined with the transition between types, it results in 3/2 x 1/2 = 3/4. Adding this to the portion originating from type 11 gives a total of 9/8 x 3/4 = 27/32. In type 13, there are two internal processing branches, so the processing result is reduced to 1/4. In type 5, the processing within the type reduces it to 3/16. Furthermore, in type 3, there are no internal branches, but it subsequently branches to either type 5 or type 13. Therefore, when the reductions from these types are combined, it is expected to converge sufficiently to less than 1. Let’s verify this in practice.

(11)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 9/8 x 3/4 = 27/32

(11)(1)(5): 3/2 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 27/128

(11)(1)(9)-(7)|(15)|(3)|(11): 9/8 x 3/4 = 27/32

(11)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 9/8 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/128

(11)(9)(3)(5): 9/8 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 243/512

(11)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 9/8 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/128

The remaining cases are (11)(9)(7): 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8, (11)(9)(11): 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8, and (11)(9)(15): 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8. However, since (11) branches to either (1) or (9) next, let’s calculate a bit further.

(11)(9)(11)(1): 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 = 27/16

(11)(9)(11)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 27/16 x 3/4 = 81/64

(11)(9)(11)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 81/64 x 3/4 = 243/256

(11)(9)(11)(1)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 81/64 x 3/4 = 243/256

(11)(9)(11)(1)(5): 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 27/16 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 81/64 x (3/16) = 243/1024

(11)(9)(11)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/8 = 81/64 x 3/8 = 243/512

(11)(9)(11) is 3/2 x 3/4 = 9/8, so if branching to (1) from here, we see that all subsequent branches have a multiplier of 1 or less. What about branching to (9)? Let’s calculate it.

(11)(9)(11)(9): 9/8 x 3/2 = 27/16

(11)(9)(11)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 9/8 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 81/64. It is easy to see that unless (3) continues, the sequence expands, requiring a considerably long path to converge to a ratio of 1 or less.

(11)(9)(11)(9)(3)(5): 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 81/64 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 729/2048

(11)(9)(11)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 27/16 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/16 = 81/64 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 729/1024

The remaining combinations are (11)(9)(7), (11)(9)(11)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), (11)(9)(15), all ending with type 7, type 11, and type 15, respectively.

When starting with integers of type 15

When starting with a type 15 integer, the subsequent transition must be either type 7 or type 15. Since consecutive type 15 transitions require separate consideration, we will examine only the transition from type 15 to type 7 here. The transition from type 15 to type 7 involves a 3/2 expansion. The transition from type 7 has already been examined. For (7)(11)(1)(9)(7), (7)(11)(1)(9)(11), (7)(11)(1)(9)(15), (7)(11)(9)(7), (7)(11)(9)(11), (7)(11)(9)(1) are expanded. Therefore, if the initial transition starts from type 15 to type 7, it undergoes an additional 3/2 expansion, resulting in a total expansion. (7)(11)(1)(9)(7), (7)(11)(1)(9)(11), (7)(11)(1)(9)(15), (7)(11)(9)(7), (7)(11)(9)(11), (7)(11)(9)(1) expand, but all others contract. However, since it has already been scaled up by a factor of 3/2 during the transition from (15) to (7), it cannot be considered a net reduction unless it is scaled down sufficiently to cancel this increase. In other words, starting from type 15 makes it harder to achieve a reduction compared to starting from type 7, due to the initial 3/2 scaling factor.

Now let’s actually check it out.

(15)(7)(3)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 81/128 (however, multiply by 3/16 in the internal processing of type 5)

(15)(7)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/64

(15)(7)(11)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 81/32

(15)(7)(11)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 81/32

All branches except (15)(7)(3)(5) are expanded, so subsequent branching must be considered.

A) First, we examine (15)(7)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15). When branching to (1)|(3)|(5)|(9)|(13) after type 13, the sequence begins to decrease. Let’s examine whether it shrinks to integers smaller than the starting integer. The simplest case is when (5)|(3)|(13).

(15)(7)(3)(13)(5): 81/64 x (3/16) = 243/1024 (however, multiply by 3/16 in the internal processing of type 5)

When (5) continues, it reduces to integers smaller than the starting integer.

Regarding (15)(7)(3)(13)(3), since (5) or (13) follows each one, let’s check them individually.

(15)(7)(3)(13)(3)(5): 81/64 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 729/2048

(15)(7)(3)(13)(3)(13): 81/64 x 3/2 x (3/8) = 729/1024

(15)(7)(3)(13) also converges easily to a ratio of 1 or less when (13) follows.

(15)(7)(3)(13)(13): 81/64 x (3/8) = 243/512

Each converges to an integer smaller than the integer that served as its starting point. Next, we examine (15)(7)(3)(13)-(1)|(9).

(15)(7)(3)(13)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 81/64 x 3/4 = 243/256

(15)(7)(3)(13)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 81/64 x 3/4 = 243/256

However, since (15)(7)(3)(13)-(7)|(11)|(15) all expand, we will temporarily postpone consideration of the subsequent columns.

B) Next, we examine (15)(7)(11)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 81/32. For (15)(7)(11)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13), since all four branching candidates are in a shrinking trend, the issue becomes how much we can reduce the previously expanded 81/32 ratio.

For (15)(7)(11)(1)(5), since they are scaled down by a factor of 3/16 in the internal processing of type 5, they are reduced all at once to proven integers smaller than the starting integer.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 243/512 (however, multiply by 3/16 in the internal processing of type 5)

For (15)(7)(11)(1)(13) as well, the transition from type 13 to the next (1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15) results in a 3/8 reduction, so it barely shrinks compared to the starting integer.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/8 = 243/256

For (15)(7)(11)(1)(1), it further branches to either (1)|(5)|(9)|(13), but since the expansion rate is 3/4, it is difficult for it to become smaller than the starting integer all at once. The same holds for (15)(7)(11)(1)(9). (15)(7)(11)(1)(9) subsequently branches to either (7), (15), (3), or (11), with an expansion rate of 3/4.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 243/128

(15)(7)(11)(1)(9)-(7)|(15)|(3)|(11): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 243/128

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 = 243/128. Regarding this, since the branch candidates (1), (5), (9), (13) all show a shrinking trend, so subsequent processing is expected to result in the overall value becoming 1 or less.

First, let’s examine the case where seemingly simple Type 5 and Type 13 follow consecutively. For Type 5, the processing within the type results in a 3/16 multiplier. Taking this internal processing into account, (15) (7)(11)(1)(1)(5): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × (3/16) = 243/128 × (3/16) = 729/2048. When Type (13) continues, branching from Type 13 to (1), or (3), (5), (7), (9), (11), (13), (15) multiplies by 3/8, so (15)(7)(11)(1) (1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/8 = 243/128 × 3/8 = 729/1024. In contrast, when Type 1 and Type 9 follow each other, it seems a bit more difficult. A single extension process only multiplies by 3/4, so it won’t reach a multiplier of 1 or less. Therefore, it seems necessary to continue this process two or three times. Let’s actually calculate it.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 243/128 x 3/4 = 729/512

It’s still not working, but when Types 5 and 13 occur consecutively, it’s straightforward. When Type 5 occurs consecutively, the problem is solved simply by considering the processing within that type. (15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(5): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × (3/16) = 243/128 × 3/4 × (3/16) = 729/512 × (3/16) = 2187/8192, converging to a proven integer smaller than the starting integer.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/8 = 243/128 × 3/4 × 3/8 = 729/512 × 3/8 = 2187/4096, thus converging to a proven integer smaller than the starting integer.

Now, let’s see what happens when Type 1 and Type 9 follow each other. Since both are multiplied by 3/4, the result seems likely to be a subtle number.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 = 243/128 × 3/4 × 3/4 = 729/512 × 3/4 = 2187/2048, which falls just short of reaching a magnification factor of 1.

In this case, too, it is straightforward when Type 5 and Type 13 follow consecutively.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(1)(5): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × (3/16) = 243/128 × 3/4 × 3/4 × (3/16) = 729/512 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 2187/2048 x 3/16 = 6561/32768. Thus, simply adding internal processing within Type 5 converged the result to a scale factor of 1 or less.

For Type 13, the sequence continues as follows: -(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15). Now let’s calculate it.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/8 = 243/128 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/8 = 729/512 × 3/4 × 3/8 = 2187/ 2048 × 3/8 = 6561/16384, which also reduces to a scale factor of 1 or less.

The problem arises when Type 1 and Type 9 occur consecutively. However, since we have already reached 2187/2048, multiplying by 3/4 more should bring the ratio down to below 1.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 243/128 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 2187/2048 x 3/4 = 6561/8192

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(1)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 243/128 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 2187/2048 x 3/4 = 6561/8192

Each branch converges to a magnification of 1 or less.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 = 243/128 × 3/4 × 3/4 = 729/512 × 3/4 = 2187/2048: Verify only the branching to Type 3, which shows a decreasing trend. For the remaining (15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15) are reserved.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(9)(3)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 243/128 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 2187/2048 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 19683/65536

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(9)(3)(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/8) = 243/128 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 2187/2048 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 19683/32768

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 = 243/128 × 3/4 = 729/512. For this, only the branch to Type 3 is considered. For the others, (15) (7)(11)(1)(1)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15) are deferred.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(9)(3)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 243/128 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 6561/16384

Here, too, it has converged to a magnification of 1 or less.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/2 × (3/8) = 243/128 × 3/4 × 3/2 × (3/8) = 6561/8192

Here again, the result converges to a multiplier of 1 or less.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(9)-(7)|(15)|(3)|(11): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 = 243/128. We will also verify the case where Type 3 continues, and leave (15)(7)(11)(1)(9)-(7)|(15)|(11) pending.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(9)(3)(5): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/2 × (3/16) = 243/128 × 3/2 × (3/16) = 2187/4096. Here too, it converges to a multiplier of 1 or less.

(15)(7)(11)(1)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/4 × 3/2 × (3/8) = 243/128 × 3/2 × (3/8) = 2187/2048. Unfortunately, this does not quite reach a magnification factor of 1 or less.

However, when (5) follows, it is internally scaled down to 3/16; when (13) follows, it is scaled down to 3/8; for (1) or (9), it is scaled down to 3/4; and for (3), it branches to either (5) or (13) afterward. Consequently, all cases will reach a multiplier of 1 or less.

When branches to (7), (11), and (15) occur consecutively as in (15)(7)(11)(1)(9)(3)(13)-(7)|(11)|(15), hold off.

C) Finally, we examine (15)(7)(11)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15). (15)(7)(11)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/2 × 3/4 = 81/32. The same processing as for (15)(7)(11)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13) will be performed. This analysis focuses solely on Type 3, which exhibits a trend of shrinking. Regarding (15)(7)(11)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), since these would further expand the trend, consideration of subsequent columns is deferred.

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 81/32 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 729/1024

When branching into type (5) via (3), it contracts to a magnification of 1 or less.

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 729/512

When branching to type (13) via (3), it cannot be contracted to a magnification of 1 or less.

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 729/512

From here on, branching to (5), branching to (13), or branching to (5) or (13) via (3) is expected to be straightforward. However, reaching (1) and (9) is just barely out of reach. -(7)|(11)|(15) is still a long way off. Now let’s actually verify this.

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x (3/16) = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x (3/16) = 729/512 x (3/16) = 2187/8192

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/8 = 729/512 x 3/8 = 2187/4096

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(3)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 729/512 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 6561/16384

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 729/512 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 6561/8192

Next, let’s calculate the branching to (1) and (9).

First, we’ll calculate the branching to (1).

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 = 729/512 x 3/4 = 2187/2048

It falls just short of a magnification of 1. However, the subsequent series from (1), (5), (9), and (13) are all decreasing sequences, so a magnification of 1 is now within reach.

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(1)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 729/512 x 3/4 x (3/16) = 2187/2048 x (3/16) = 6561/32768 (however, multiply by 3/16 in the internal processing of type 5)

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(1)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x 3/8 = 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/8 = 2187/2048 x 3/8 = 6561/16384

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(1)(1)-(1)|(5)|(9)|(13): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 2187/2048 x 3/4 = 6561/8192

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(1)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 2187/2048 x 3/4 = 6561/8192

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(9) is similar to (15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(1), but the subsequent branches to (3), (7), (11), and (15) exhibit an expansion tendency except for the case of (3), making it difficult. Here, we will only confirm the branch to type (3), leaving the branches to (7), (11), and (15) pending.

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(9)-(3)|(7)|(11)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 = 729/512 x 3/4 = 2187/2048

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(9)(3)(5): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16)= 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/2 x (3/16)= 2187/2048 x 3/2 x (3/16) = 19683/65536

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15): 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 81/32 x 3/2 x 3/8 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8= 729/512 x 3/4 x 3/2 x 3/8= 2187/2048 x 3/2 x 3/8 = 19683/32768

(15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)-(7)|(11)|(15) shall also be deferred.

Review of items left on hold

As a result of our previous discussions, we have left the following as pending: Type 7 starting with (7)(11)(1)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), (7)(11)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), as well as those starting with Type 11: (11)(9)-(7)|(15) and (11)(9)(11)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), and those starting with Type 15: (15)(7) (3)(13)-(7)|(11)|(15), (15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(1)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), (15)(7)(11)(1)(1)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), (15)(7)(11)(1)(9)(3)(13)-(7)|(15)|(11), (15)(7)(11)(1)(9)-(7)|(15)|(11), (15)(7)(11)(9) (3)(13)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), (15)(7)(11)(9)(3)(13)-(7)|(11)|(15), (15)(7)(11)(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), and (15) are consecutive. Each is a sequence that begins with Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15, and ends with Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15. Our previous verification has shown that not all columns starting with Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15 are expansion columns.

Let’s determine the overall proportion of items left on hold. We found that all sequences starting with types 1, 3, 5, 9, and 13 converge to a multiplier of 1 or less. In other words, 5/8 converges immediately. In contrast, it has been found that sequences starting from Types 7, 11, and 15 do not necessarily converge immediately. Let us calculate how much of 3/8 remains as a divergent sequence.

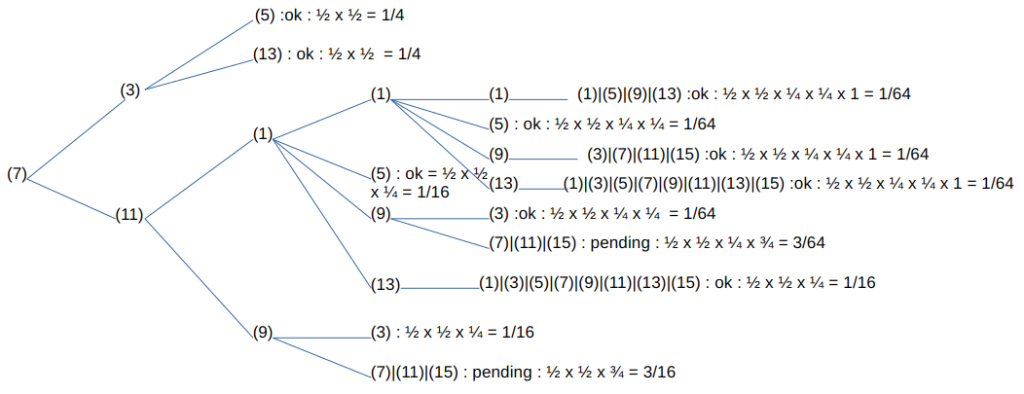

The final branch shows whether to shrink or hold as an expansion sequence, along with the occurrence rate for each case. If shrinking results in a magnification of 1 or less, it displays “ok”; if holding as an expansion sequence, it displays “pending”.

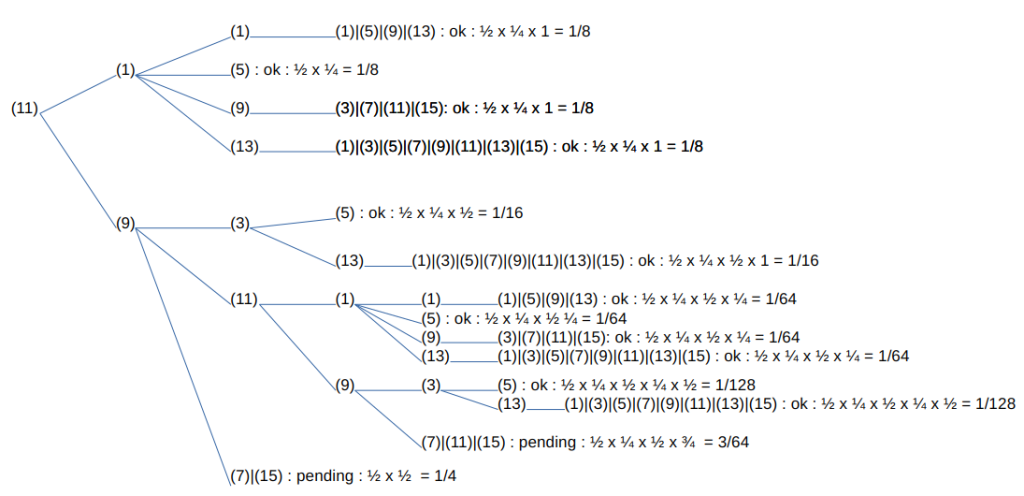

Next, let’s consider the case where 11 comes first.

The occurrence rate of the column held due to the expanding trend is 3/64, and combined with 1/4, this totals 19/64. Since the initial occurrence of Type 11 is 1/8 times, the total becomes 1/8 × 19/64 = 19/512.

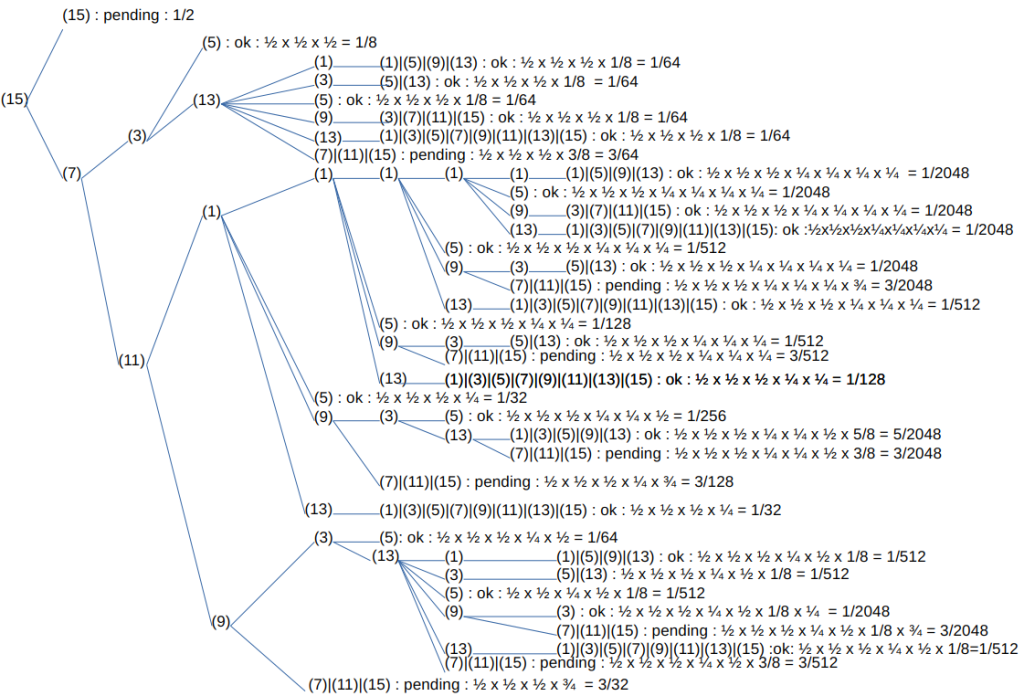

Next, let’s calculate the case where starting from Type 15.

Although only Type 15 has been added before Type 7, it immediately becomes clear that the structure is significantly more complex compared to the diagram for Type 7. Because Type 15 comes first, it is multiplied by 3/2 initially. Consequently, even if a reduction sequence follows, it cannot necessarily offset the initial 3/2 effect. This makes the structure more difficult compared to when Type 7 comes first.

Now, let’s calculate the case where Type 15 comes first. First, we branch to (7)|(15). Here, we do not consider the loop for (15). This is because the Type 15 loop always transforms into Type 7. We will prove this later. Therefore, we only consider the branch from Type 15 to Type 7 here, and the loop for (15) is not included in the calculation for pending cases either. Adding the cases that are held: 3/64 + 3/2048 + 3/512 + 3/2048 + 3/128 + 3/2048 + 3/512 + 3/32 = 269/2048. Since the initial proportion of Type 15 is 1/8, the overall proportion is 269/16384.

The hold rate when starting from Type 7 is 15/512, the hold rate when starting from Type 11 is 19/512, and the hold rate when starting from Type 15 is 269/16384. Averaging these gives (15/512 + 19/512 + 269/16384)/3 = ( (480 + 608 + 269)/16384)/3 = (1357/16384)/3 = 0.082824707/3 = 0.027608236 ≈ 1/40

When starting with Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15 and ending with an expansion trend, all end with Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15. Continuing the Collatz operation on these yields results slightly different from the initial calculation. Initially, the proportions starting with Type 7, Type 11, and Type 15 are each 1/8. However, in subsequent calculations after holding Type 7, Type 11, and Type 15, this 1/8 is not included in the calculation. Therefore, the proportion of the expansion trend becomes: (15/64 + 19/64 + 269/2048)/3 = ((480 + 608 + 269)/2048)/3 = 0.220865885 ≒ 1/5. The initial calculation showed that 39 out of 40 overall were decreasing, while 1 out of 40 was expanding further. This is because the Collatz operation continues from this expanding portion of 1/40 to the branches for Types 7, 11, and 15.

Type 7 branches into either (3) or (11), with (3) showing a declining trend. Type 11 branches into either (1) or (9), both showing a declining trend. In contrast, Type 15 branches into either (7) or (15), both showing an expanding trend.

When we add subsequent columns to the expanding column, the result looks like this.

Unless (15) occurs consecutively, the sequence will continue to show a decreasing trend. Of course, even if the decreasing trend continues, it does not necessarily mean the ratio will immediately fall below 1. This is because once expansion occurs, simple calculations become impossible. For example, if a sequence ending with (7) is followed by (11)(9), it contracts. However, if (9) is followed by -(7)|(11)|(15), it expands again. Even if it continues as (11)(9)-(3), it cannot be definitively stated that the ratio will contract to 1 or below. For example, when branching into (11)(9)(3)(13)-(1)|(3)|(5)|(7)|(9)|(11)|(13)|(15), the multiplier usually becomes 1 or less here. However, if it unfortunately does not, the sequence may revert to an expansion trend from (11)(9)(3)(13)-(7)|(11)|(15), it may shift back toward expansion. In other words, when an expansion-tendency sequence is followed by a subsequent sequence, even if that sequence is contraction-tendency, it becomes crucial whether it can cancel out the multipliers of the preceding sequences and bring the total back to a multiplier of 1 or less. The only thing that can be said with certainty is that no matter what sequence follows, the number of sequences ending with (15) will definitely increase, leading to a multiplier of 1 or less.

Ratio of even and odd numbers in the second digit

When resuming calculations from a point where they were temporarily paused as pending, let us consider the branching to (7), (11), and (15), specifically the evenness or oddness of the second digit at that point. This is because if the ratio of even to odd outcomes is equal, the reduction can be simply calculated as 4/5 and the expansion rate as 1/5.

First, we will consider combinations with the second digit, assuming the third digit is “0”. It is crucial to remember the carry-over from the first digit. A carry-over occurs when the first digit is an odd number between 5 and 15, while no carry-over occurs for 1 and 3. Therefore, the ratio for carry-over is 6/8, and the ratio for no carry-over is 2/8.

3<0, 1> = <0, 3>. If there is no carry from the first digit, the second digit is decremented by 1 to divide by 2 (resulting in the first digit being incremented by 16), yielding <0, 2>. If there is a carry, it becomes <0, 4>. Dividing each by 2 gives <0, 2> → <0, 1> and <0, 4> → <0, 2>. Thus, <0, 1> occurs 1/4 of the time, and the remaining 3/4 become <0, 2>.

3<0, 2> = <0, 6>. Since the first digit should always be even as a result of the (3n+1)/2 processing, we simply divide by 2 to get <0, 3>.

Performing the same calculation yields the following result.

3<0, 3> = <0, 9>. For the 1/4 case with no carry from the first digit, <0, 8/2> = <0, 4>. For the 3/4 case with a carry from the first digit, <0, 10/2> = <0, 5>.

3<0, 4> = <0, 12> → <0, 6>

3<0, 5> = <0, 15>. For the 1/4 case with no carry from the first digit, <0, 14/2> = <0, 7>. For the 3/4 case with a carry from the first digit, <0, 16/2> = <0, 8>.

3<0, 6> = <0, 18> → <0, 9>

3<0, 7> = <0, 21>. For the 1/4 case with no carry from the first digit, <0, 20/2> = <0, 10>. For the 3/4 case with a carry from the first digit, <0, 22/2> = <0, 11>.

3<0, 8> = <0, 24> → <0, 12>

3<0, 9> = <0, 27>. For the case of 1/4 with no carry from the first digit, <0, 26/2> = <0, 13>. When there is a carry from the first digit, <0, 28/2> = <0, 14>.

3<0, 10> = <0, 30> → <0, 15>

3<0, 11> = <0, 33>. For the case of 1/4 with no carry from the first digit, <0, 32/2> = <0, 16> = <1, 0>. When there is a carry from the first digit, <0, 34/2> = <0, 17> = <1, 1>.

3<0, 12> = <0, 36> → <0, 18>

3<0, 13> = <0, 39>. For the case of 1/4 without a carry from the first digit, <0, 38/2> = <0, 19> = <1, 3>. When there is a carry from the first digit, <0, 40/2> = <0, 20> = <1, 4>.

3<0, 14> = <0, 42> → <0, 21>

3<0, 15> = <0, 45>. For the case of 1/4 without a carry from the first digit, <0, 44/2> = <0, 22> = <1, 6>. When there is a carry from the first digit, <0, 46/2> = <0, 23> = <1, 7>.

When the second digit is even, the operation alternately produces odd and even numbers. That is, the occurrence ratio of odd and even numbers is the same. When the second digit is odd, for <0, 1>, <0, 5>, <0, 9>, and <0, 13>, odd numbers occur 1/4 of the time and even numbers 3/4 of the time. For cases <0, 3>, <0, 7>, <0, 11>, and <0, 15>, conversely, even numbers occur at a rate of 1/4 and odd numbers at a rate of 3/4. Here, too, it is found that overall, odd and even numbers appear in the same proportion.

(7), (11), and (15) also do not always follow this pattern. Sometimes (1), (5), (9), or (13) may occur in between. In these cases, the division by 2 process is added within this pattern. It is added once for (1) and (9), twice for (13), and at least four times for (5). Additionally, in case (3), internal processing is added by going through (5) or (13). Within this type, the processing is simply division by 2. The prerequisite is that the first digit is an even number between 0 and 14. Since it is only division by 2, there is no carry from the first digit. However, if the second digit is odd, the process requires subtracting 1 from the second digit and adding 16 to the first digit. Now, let’s calculate the “divide by 2” process for.

<0, 0> → <0, 0>

<0, 1> → <0, 0>

<0, 2> → <0, 1>

<0, 3> → <0, 1>

<0, 4> → <0, 2>

<0, 5> → <0, 2>

<0, 6> → <0, 3>

<0, 7> → <0, 3>

<0, 8> → <0, 4>

<0, 9> → <0, 4>

<0, 10> → <0, 5>

<0, 11> → <0, 5>

<0, 12> → <0,6>

<0,13> → <0, 6>

<0, 14> → <0, 7>

<0, 15> → <0, 7>

Of the 16 possibilities, 8 have an even second digit, and 8 have an odd second digit, resulting in an identical ratio.

It was found that whether processing (3n+1)/2 or simply “/2” (division by 2), the ratio of whether the second digit becomes even or odd is the same.

Let’s try adding more digits.

Thus far, we have considered the first digit as an odd number between 0 and 15 for the (3n+1)/2 process, and as an even number between 0 and 14 for the “divide by 2” (/2) process. The third digit starts as “0” at the beginning of the calculation. Now, let us consider the case where the third digit is between 1 and 15. In this case, when processing (3n+1)/2 or “/2”, adjustments to the third and second digits become necessary. Adjustments shall be made first between the first and second digits, then between the second and third digits. Assume the first and second digits have already been adjusted and are both even. In the (3n+1)/2 processing, the first digit should initially range from 0 to 46, while the second and third digits should initially range from 0 to 45. However, when the digit count falls between 16 and 31, subtract 16 from the original digit and increment the higher digit by 1. When the number of digits is “32 to 45 (or 46)”, subtract 32 from the original digit and increment the upper digit by 2. Assume all digit values are already within the range “0 to 15”. During this adjustment, the ratio of even to odd digits in the lower positions remains unchanged. This is because the adjustment only involves ±16 or ±32.

If the third digit is even, simply dividing by 2 suffices. However, if the third digit is odd, a problem arises. When the third digit is odd, the process of adding 16 to the second digit and subtracting 1 from the third digit is necessary. After performing this operation and then dividing by 2, the ratio of whether the second digit becomes even or odd is the same. This is because adding 16 to the second digit does not affect whether the result is even or odd when divided by 2. Therefore, the conclusion that the ratio of even to odd results is the same holds, identical to the calculation performed above.

When (1) and (9) occur consecutively, an additional “/2” operation is performed. In this case, since the first digit should already be even, the second digit is adjusted to make it even. Then, if the third digit is odd, the second digit is increased by 16, and the third digit is decreased by 1. For (13), an additional division by 2 is performed. In this case, the previous +16 applied to the second digit becomes +8 due to the first division by 2, and the result of the new operation is added. If the third digit is odd before the second division by 2, +16 is added, resulting in division by 2 yielding +8 + 4. When branching to (5), an additional division by 2 is performed. Considering all cases where the third digit is odd or even within each internal process, the results become +8+4+2, +8+2, +8+4, +8, +4+2, +4, +2, etc. In any case, this does not affect whether the second digit is even or odd. However, if we consider that adjustments are made between each digit during each processing step, there is no need to treat the first internal processing and the second internal processing as separate entities.

What happens to even and odd numbers in the processing of (3n+1)/2 and /2?

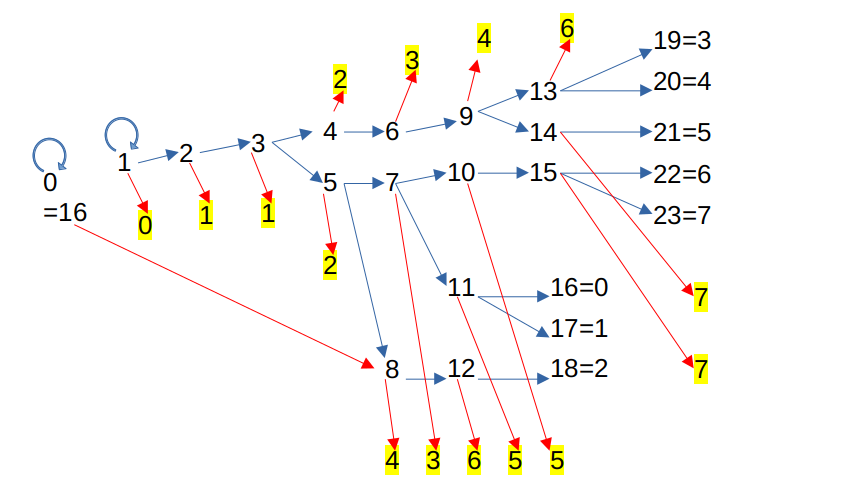

Let’s examine how each digit changes through the processing of (3n+1)/2 and “/2”. Note that we are considering digits starting from the second digit onwards, so the actual calculation for (3n+1)/2 is 3n/2. 3n/2 is represented by the blue arrows, while the “/2” processing is shown by the red arrows. Even numbers fall into two categories: 0, 4, 8, 12 result in both digits being even, while 2, 6, 10, 14 result in both digits being odd. Odd numbers fall into three categories: 1, 5, 9, 13, which result in 2/3 of the digits being even and 1/3 being odd. In contrast, for 3, 7, 11, and 15, two-thirds are odd, and one-third are even. Therefore, whether the number is even or odd, the ratio of digits becoming even or odd after applying 3n/2 and the “/2” processing is the same.

Looking at the type transition diagram, we see that all branches depend on whether the second digit is even or odd. For example, suppose the second digit is currently 1. Each time the Collatz operation processes (3n+1)/2 (actually 3n/2 for two or more digits), the second digit changes. This change follows the pattern shown in the tree diagram above. While the even and odd digits do not always change at the same rate, overall, the branches where the second digit is even occur at the same rate as the branches where the second digit is odd.

This holds for 4-digit integers, 5-digit integers, and 6-digit integers as well. The process of 3n/2 and the “/2” operation simply involves adjusting the digits in pairs, starting from the least significant digit, to make the number of digits even, and then dividing by 2. As we have already seen, performing this operation results in the second digit being even or odd with the same probability.

That concludes the adjustments for the digit immediately below. Now let’s consider adjustments for the digit above. Suppose all digits have been adjusted to 0–15, and further, that we’ve sequentially adjusted the lower digits to even numbers. At this stage, if the digit above the target digit is odd, the digit above is decremented by 1, and the target digit is incremented by 16. After one “divide by 2” operation, this +16 becomes +8. For Type 1 and Type 9, one more “divide by 2” operation is added. At this point, if the digit above is even, it becomes +4; if odd, it becomes +8 + 4. For Type 13, an additional “divide by 2” operation is performed. Consequently, the change to the digit in question becomes one of the following: +8+4+2, +8+4, +8+2, +4+2, +8, +4, or +2. In any case, the parity (even or odd) of the digit in question remains unchanged.

Now, let’s verify what happens when (3n/2)(/2), or (3n/2)(/2)(/2), is followed by an additional (3n/2). The following shows the case of (3n/2)(/2)(/2).

Now, let’s verify what happens when (3n/2)(/2), or (3n/2)(/2)(/2), is followed by an additional (3n/2). Next, we show the case for (3n/2)(/2).

3(+8+4)/2 = 36/2 = 18 → 18-16=2

3(+8)/2 = 24/2 = 12

3(+4)/2 = 12/2 = 6

The digits that have been shifted down remain even, so the original digits’ even or odd status remains unchanged.

The following shows the case of (3n/2)(/2)(/2).

3(+8+4+2)/2 = 42/2 = 21 → 21-16=5

3(+8+2)/2 = 30/2 = 15

3(+4+2)/2 = 18/2 = 9

3(+2)/2 = 6/2 = 3

In either case, the digit that moves down becomes odd, causing the even-odd status of that digit to switch. However, since this is merely a switch, the ratio of even to odd remains unchanged from before.

Tracking the extended column further

As previously shown, when applying the Collatz operation starting from type 7, 15/512 was retained as the expansion tendency. Removing the initial 1/8 yields a reduction-to-expansion ratio of 49/64: 15/64 = 49: 15. The retention rate when starting from type 11 is 19/512. Removing the initial 1/8 yields a reduction-to-expansion ratio of 45/64 : 19/64 = 45 : 19.

Since we know that Type 15 eventually becomes Type 7 (this will be proven later), let’s consider the rate at which Type 15 becomes Type 7 and then enters a holding state. This can be calculated by subtracting half of the rate for consecutive Type 15s from 1393/2048: 1393/2048 – 1/2 = (1393-1024)/2048 = 369/2048. The ratio of reduction to expansion is 1679: 369 = 4.550135501: 1 ≒ 9: 2.

Type 11 becomes Type 1 when the second digit is even, and Type 9 when it is odd. After this, it tends to decrease, and while continuing to expand and contract thereafter, it generally becomes a smaller integer. The hold rate starting from Type 11 is 19/64, and 45/64 converges to a multiplier of 1 or less. So, what happens if we start the next operation from the point where we paused? When processing resumes from that paused point, it will restart from either Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15. The reduction ratio at this point is 4/5, and the expansion ratio is 1/5. When restarting from a reduction trend, the reduction ratio again becomes 45/64 and the expansion ratio 19/64. When restarting again from Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15, the reduction ratio is 4/5, and the expansion ratio is 1/5. This pattern repeats. A diagram of this process is as follows.

We define a “series of Collatz processes” as the sequence of Collatz steps that begins by reaching Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15, and ends when the process is restarted. The number 45/64, reduced in the first such series, has been scaled down to a factor of 1 or less. Therefore, in the second “series of Collatz processes,” calculations continue only for the sequence that expanded to reach Type 7, Type 11, and Type 15 before being suspended and restarting from the point where calculations were suspended results in computations originating from Type 7, Type 11, and Type 15, yielding a reduction rate of 4/5 and an expansion rate of 1/5. Regarding the columns showing a shrinking trend, some may have already reached a magnification ratio of 1 or less, but this is not currently factored into the calculations. Furthermore, restarting from a shrinking trend constitutes a normal restart (i.e., not a restart from a halted state after reaching Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15). Therefore, the shrinkage rate is 45/64, and the expansion rate is 19/64.

The question is whether we should consider the overall process as contracting when the number of contracting sequences (a series of Collatz operations) equals the number of expanding sequences (those halted after reaching Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15). While a single Collatz operation can be evaluated as growing at a rate of 3/2 and contracting at 4/3, what we are considering here is the continuous sequence of Collatz operations until a halt is determined. Let’s examine this using Type 11. The cases left pending in Type 11 are (11)-(9)-(7)|(15) and (11)-(9)-(11)-(9)-(7)|(11)|(15). The ratio of (11)-(9)-(7)|(15) is 3/2 × 3/4 = 9/8, and the ratio of (11)-(9)-(11)-(9)-(7)|(11)|(15) is 3/2 × 3/4 × 3/2 × 3/4 = 81/64. What is the reduction ratio? Since the reduction rate is scaling down the 3/2 from the initial starting point (11) at the branch (11) – (1) | (9) to a factor of 1 or less, it can be considered 2/3. Then, 9/8 × 2/3 = 18/24 and 81/64 × 2/3 = 162/192, both of which have a factor of 1 or less. Considering the above, when the number of expansions and contractions is equal for RE and ER, it can be said that contraction is occurring.

Based on the above considerations, the reduction rate is calculated as follows.

End of the first series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:45/64 = 0.703125

End of the second series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 = 0.703125 + 0.2375 = 0.940625

End of the third series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 = 0.870117

End of the fourth series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:45/64 + (19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 19/64) + 19/64 x 4/5 x 19/64 x 4/5 + 19/64 x 1/5 x 4/5 x 45/64 = 45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 19/64 x 4/5 + 19/64 x 1/5 x 4/5 x 45/64 = 0.870117 + 19 x 4(74 + 45)/(64x5x64x5) = 0.870117 + 0.089805 = 0.959922

End of the fifth series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:45/64 + (19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 45/64 x 45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 45/64 x 19/64) + 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 19/64 x 4/5 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 + 19/64 x 1/5 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 45/64 = 45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 45/64 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 19/64 x 4/5 + 19/64 x 4/5 x 19/64 x 4/5 x 45/64 + 19/64 x 1/5 x 4/5 x 45/64 x 45/64 = 0.703125 + 19x4x452/643x5 + (42x192x45 + 42x192x45 + 4x19x452)/52x643 = 0.703125 + 0.123097 + 0.102804 = 0.929026

The reduction rate decreased slightly between the second and third iterations. This occurs because when the number of reductions equals the number of expansions, the reduction rate increases in even-numbered iterations compared to odd-numbered ones. When viewed in terms of even and odd iterations, the rate of reduction gradually increases as the sequence of Collatz steps progresses. Furthermore, as the sequence shrinks, some terms will reach a multiplier of 1 or less, eliminating the need for further calculations. Consequently, the actual rate of reduction will be even greater than this calculated value.

The same reasoning applies to Type 7. After the first “series of Collatz processes,” 15/64 shrinks to a multiplier of 1 or less, while 49/64 exhibits an expansion tendency and is suspended mid-calculation. When restarting calculations for the suspended cases, the restart point becomes either Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15. At this point, the contraction rate is 4/5, and the expansion rate is 1/5.

For Type 7, the combinations left pending are (7)-(11)-(1)-(9)-(7)|(11)|(15) and (7)-(11)-(9)-(7)|(11)|(15). For (7)-(11)-(1)-(9)-(7)|(11)|(15), the multiplier is 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 x 3/4 = 81/64. For (7)-(11)-(9)-(7)| (11)|(15) is 3/2 x 3/2 x 3/4 = 27/16. When the number of reductions and expansions is equal, the ratios become 81/64 x 2/3 = 162/192 and 27/16 x 2/3 = 54/48. The occurrence rate is 162/192 at 3/64 and 54/48 at 3/16. Considering the occurrence rates, the expansion factor becomes (162/192 x 1/5 + 54/48 x 4/5) = 1026/960, indicating a slight expansion. Therefore, when starting from Type 7, if the number of contraction sequences equals the number of expansion sequences, we treat it as an expansion case. Based on the above analysis, the contraction rate is calculated as follows.

End of the first series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:49/64 = 0.765625

End of the second series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:49/64 = 0.765625

End of the third series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:49/64 + 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 = 0.765625 + 0.143554 = 0.909180

End of the fourth series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:49/64 + 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 49/64 = 0.765625 + 0.109909 = 0.875534

End of the fifth series of Collatz processes:

Reduction ratio:49/64 + (15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 49/64 x 49/64 + 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 49/64 x 15/64) + 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 15/64 x 4/5 + 15/64 x 4/5 x 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 + 15/64 x 1/5 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 49/64 = 49/64 + 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 49/64 + 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 15/64 x 4/5 + 15/64 x 4/5 x 15/64 x 4/5 x 49/64 + 15/64 x 1/5 x 4/5 x 49/64 x 49/64 = 0.765625 + 0.109909 + (42x152x49 + 42x 152x49 + 4x15x492)/(52x643) = 0.765625 + 0.109909 + 0.04217 = 0.917703

For Type 7, we can see that the reduction rate gradually increases while fluctuating. In Type 7, when the number of reduction steps and expansion steps was equal, it was treated as an expansion, causing the reduction rate to drop on even-numbered iterations. However, when looking only at even-numbered iterations or only at odd-numbered iterations, we can see that the reduction rate gradually increases with each successive Collatz process. Furthermore, as mentioned when discussing Type 11, if the reduction sequence converges to a magnification of 1 or less, the proof is considered complete at that point, and subsequent calculations are not performed. Therefore, the actual reduction rate is higher than the calculated result above.

The same holds for Type 15. Whether you judge a case where the number of occurrences of the shrinking sequence and the expanding sequence is equal as a shrinkage or an expansion, the overall shrinkage rate increases the more Collatz processes are performed. Therefore, the same applies to Type 15.

Modeling Type 7 and Type 11

In the calculations up to this point, to ensure greater accuracy, we treated reductions and expansions from the reduction sequence separately from reductions and expansions during recalculation after temporarily holding items as expansion sequences. This made the calculations complex. Here, let’s try calculating reductions and expansions within the reduction sequence together with reductions and expansions when restarting after temporarily holding items as expansion sequences, using the same rate for both. When starting from Type 7, Type 11, or Type 15, the expansion rate averages 1/5, so the reduction rate is 4/5. Let’s base our calculations on this.

The total reduction rate after performing a sequence of 6 Collatz operations is as follows.

When n = 1

4/5

When n = 2

4/5 +(1/5)x (4/5)

When n ≥ 3 and n/2 = integer (However, r ≦ (n+1)/2)

4/5 +(1/5)x (4/5)n-1 + n-1C1(4/5)n-2(1/5) + …… + n-1Cr(4/5)n-r-1(1/5)r

When n ≥ 3 and (n-1)/2 = integer (However, r < (n-1)/2)

4/5 + (1/5)x(4/5)n-1 + n-1C1(4/5)n-2(1/5) + …… + n-1Cr(4/5)n-r-1(1/5)r

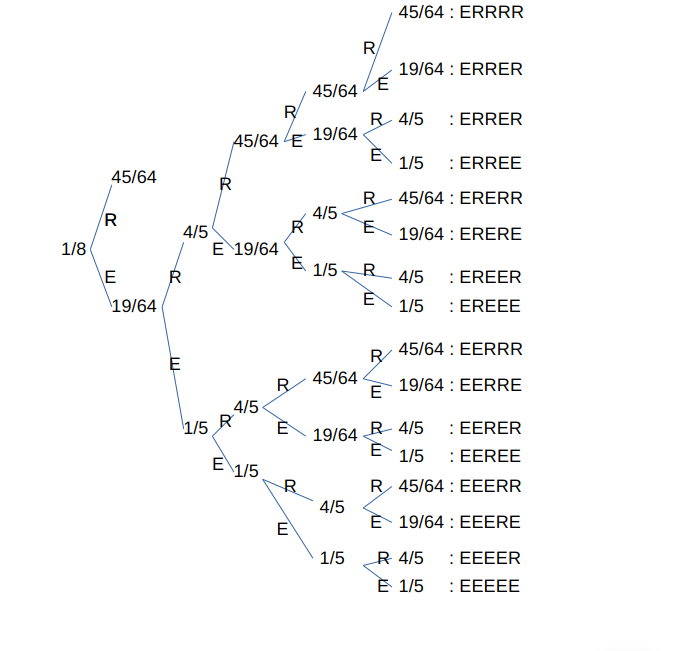

Let’s examine the fourth iteration of the Collatz process. Here, among the sequences obtained through the Collatz process, if the number of reductions equals the number of expansions, we consider it a reduction. In terms of reduction rates, we can classify them as follows: ERRR (3 reductions, 1 expansion), ERRE, ERER, EERR (2 reductions, 2 expansions), EREE, EERE, EEER (1 reduction, 3 expansions), and EEEE (0 reductions, 4 expansions). Here, let ERRR be denoted by A, with a reduction rate of a. Let ERRE, ERER, and EERR be denoted by B, C, and D, respectively, with reduction rates b, c, and d, respectively. Furthermore, let EREE, EERE, and EEER be denoted by E, F, and G, respectively, with reduction rates e, f, and g, respectively. At this point, the total reduction rate becomes 4/5 + a + b + c + d. The fifth reduction does not necessarily have an equal number of shrinking and expanding sequences. Therefore, three reductions followed by two expansions count as a reduction, while two reductions followed by three expansions count as an expansion. Thus, the total reduction rate for the fifth step is 4/5 + a x 4/5 + a x 1/5 + (b + c + d) x 4/5 = 4/5 + a + (b + c + d) x 4/5. This means the total reduction is (b + c + d) x 1/5. Since the sixth time is considered a contraction when the same number of contractions and expansions occur, the total contraction rate is as follows. 4/5 + a x 4/5 + a x 1/5 + (b + c + d) x (4/5)² + (b + c + d) x 4/5 x 1/5 + (b + c + d) x 1/5 x 4/5 + (e + f + g) x (4/5)² = 4/5 + a + (b + c + d) x 4/5 + (e + f + g) x 16/25. Compared to the fifth iteration, the reduction rate increases by (e + f + g) x 16/25. Since b, c, and d are each (4/5)² x (1/5)², and e, f, and g are each (4/5) x (1/5)³, we have (b + c + d) : (e + f + g) = 4 : 1. Therefore, (a + b + c) x 1/5 : (e + f + g) x 16/25 = 4/5 : 16/25 = 5 : 4. Thus, the reduction rate is 4/5 + a, where a = 1/5 x 4/5 = 4/25. Thus, the rate alternates between increasing and decreasing at even and odd intervals, but the amplitude of this fluctuation gradually diminishes, ultimately approaching 24/25. Furthermore, some numbers in the shrinking sequence reach a multiplier of 1 or less during a “series of Collatz steps.” Let’s denote this rate as α. The reduction rate then becomes 24/25 + α. As more “series of Collatz steps” are applied, α increases progressively. Consequently, 24/25 + α eventually reaches 1. In other words, for Type 7 and Type 11 integers, the more Collatz operations applied, the more numbers shrink below a multiplier of 1. Eventually, all Type 7 and Type 11 integers converge to 1. The same holds for Type 15 integers.

However, the case where Type 15 branches into a loop back to Type 15 remains unproven. Subsequently, we will prove that a sequence of Type 15 numbers eventually becomes Type 7 numbers, provided the sequence contains only a finite number of integers. Furthermore, since we have proven that all two-digit integers converge to 1, we have demonstrated that for any finite sequence of integers, applying the Collatz operation sequentially starting from the smallest integer will lead to convergence to 1.

Transition from 15 Types

Type 15 branches based on whether it is followed by Type 7 or another Type 15. Therefore, it is simply multiplied by 1.5. Repeating Type 15 n times results in a simple calculation of (1.5)^n times expansion.

Here, we discuss whether it is possible to escape the sequence of Type 15. As can be seen from the type transition diagram, the <even number, 15> type transitions to Type 7 in the next transition, but the <odd number, 15> type repeats Type 15.

From here on, we will denote and perform calculations using the expression an16n + an-116n-1 + … + a116 + a0 as <<<, an-2>, …, a1>, a0>. Up to this point, we have separated ( ) and < > for explanatory convenience. Hereafter, we will use < > for the purpose of simplifying the notation.

Type 15 transitions as follows.

Even for Type 15, integers of the form <<…, 1>, 15>, <<…, 5>, 15>, <<…, 9>, 15>, <<…, 13>, 15> transition to the <evem number, 15> type after one Collatz operation. Therefore, they should transition to Type 7 in the next operation.

The problem is of the type <<…, 3>, 15>, <<…, 7>, 15>, <<…, 11>, 15>, <<…, 15>, 15>.

Among these, the <<…, 3>, 15> and <<…, 11>, 15> types are acceptable. This is because the <<…, 3>, 15> type will become either <<…, 5>, 15> or <<…, 13>, 15> in the next operation, becoming the <even number, 15> type, and then transitioning to type 7 in the subsequent operation. Similarly, <<…, 11>, 15> transitions to either <<…, 1>, 15> or <<…, 9>, 15> in the next operation. It then becomes <even number, 15> in the following operation and transitions to type 7 thereafter.

The <<…, 7>, 15> type becomes either <<…, 3>, 15> or <<…, 11>, 15> in the next operation. Then, as explained above, <<…, 3>, 15> becomes either <<…, 5>, 15> or <<…, 13>, 15> in the next operation, becoming <even number, 15> in the following operation, and transitioning to type 7 in the subsequent operation. Similarly, <<…, 11>, 15> becomes <<…, 13>, 15> in the next operation, becoming <even number, 15> in the following operation, and transitioning to type 7 in the subsequent operation. 13>, 15>, and then becomes in the next operation, transitioning to type 7 in the subsequent operation. Similarly, <<…, 11>, 15> becomes <<…, 1>, 15> or <<…, 9>, 15>, then becomes the <even number, 15> type, and can transition to type 7.

The problem is the <<…, 15>, 15> type. This type transitions to either the <<…, 7>, 15> type or the <<…, 15>, 15> type. As previously explained, the <<…, 7>, 15> type is known to eventually transition to type 7.

However, if 15 appears consecutively like <<…, 15>, 15>, there is a possibility that it cannot escape from Type 15. Let’s confirm this point next.

Considerations Regarding Consecutive Occurrences of 15 Starting from the Least Significant Digit

When 15 occurs consecutively starting from the least significant digit, the operation performed during the 3n+1 process—adding 45+1=46 to the least significant digit—and the “+1” applied to the upper digit when carrying the 46 from an intermediate digit function identically (45+1=46, which then triggers the carry to the next higher digit). Therefore, after the carry, the original digit becomes 46-16=30. Dividing this by 2 results in 15.

Breaking away from the Type 15 series

At first glance, when the coefficient for each digit is 15, it seems like the 1.5 multiplier would continue forever, but that is not the case. Since the Collatz conjecture deals with finite integers, there must always be a leading digit. And the digit immediately preceding the leading digit is 0. Therefore, the sequence should be: <<<<<<0, 15>, 15>, …>, 15>. This represents <even number, 15>, so the next Collatz operation transitions it to type 7.

How to escape from the 15-type is illustrated below. From <<<0, 15>, 15>, …>, 15>, it takes four Collatz operations for the sequence of 15s to decrease by one and for the digit that was 15 to change to an even number. In other words, <<<0, 15>, 15>, …>, 15> is equivalent to <<even number, 15>, …>, 15>. Thus, one operation reduces the number of 15s by one, resulting in <<<1, 7>, 15>, …>, 15>. From here, three operations are needed to transition to <<<…, even number>, 15>, …>, 15>. Thus, a total of four operations are required to reduce the length of a sequence of consecutive 15s by one. Consequently, for example, if a 100-digit integer consists entirely of 15s, escaping the sequence of 15s will require expanding it by approximately (1.5)⁴⁰⁰ times.

We have examined the case where 15 is repeated from the least significant digit.

Considerations Regarding the 15 in the Middle of the Digits

The case where 15 appears consecutively, starting from the least significant digit, is troublesome, but 15 may also appear intermittently. How should we approach this? For example, cases like <<<<…, (any number from 0 to 14)>, 15>, 15>, (any number from 0 to 14)>, …>. If the least significant digit is 1, 9, 13, or 5, the subsequent division by 2 will occur twice (for 1 and 9), three times (for 13), or four times or more (for 5). Consequently, the intermediate number 15 will quickly transform into another number. Similarly, the life of 15 is short in the cases of 7, 11, and 15. Fundamentally, the reason 15 appears consecutively when it starts from the least significant digit is that the carry from 15 performs the same function as the “+1” operation in the (3n+1)/2 calculation. For example, 15 × 3 + 1 = 46. Carrying the 16 to the next digit makes the least significant digit 30. The digit above that becomes 45 + 1 = 46. This digit then carries to the next higher place value, making it 30, and the digit above it becomes 45 + 1 = 46, causing another carry. Finally, when dividing by 2, the sequence of 30s is completely replaced by 15s. However, the situation differs for the 15 in the middle, as it doesn’t necessarily carry over from the digit below. The middle 15 is multiplied by 3 to become 45, but a carry from the digit below may not be expected. In that case, during the division by 2, the adjustment between digits might result in 46/2 = 23, where 23 = 16+7, yielding 7. Alternatively, it might result in 44/2 = 22, where 22 = 16+6, yielding 6. Or, coincidentally, a carry might occur from the digit below, resulting in 46. This 46 then carries itself, becoming 30, which, when divided by 2, becomes 15. However, this too is only temporary. This is because the process of dividing by 2 twice is specific to Types 7, 11, and 15. Type 7 then becomes either Type 11 or Type 3, Type 11 then becomes either Type 1 or Type 9, and Type 3 then becomes either Type 5 or Type 13. Therefore, the case where the process of dividing by 2 occurs only once does not persist indefinitely. Of course, there is an exception when Type 15 is in the least significant digit, but as already explained, this does not continue indefinitely. Furthermore, while 15 may suddenly appear where it previously did not exist, it too eventually disappears without notice.

Therefore, it can be seen that any 15 appearing in intermediate digits—except for a continuous sequence of 15 starting from the least significant digit—will vanish immediately within two or three Collatz iterations.

Transition from other types to Type 15

Transitions to Type 15 can occur from types other than Type 15. Examining the type transition diagram, at <even number, 9> – <t, 14>, when t is odd, it transitions to <u, 15>. Furthermore, at <odd number, 13> – <t, 12>, when t is odd, it transitions to <u, 14>. Additionally, when u is odd, it transitions to <v, 15>.